In the Clouds

Clouds in art from the 1800s to our own time

Enjoy a 360 presentation of the exhibition!

We are, all of us, surrounded by clouds, both in the sky above and to an ever-greater extent by cloud computing. The exhibition In the Clouds presents works from the 1800s to our own time. Using diverse approaches to science and technology, many of the works reflect themes of current interest at the time they were made. They show, among other things, how clouds can be seen as carriers of dreams, ideas, freedom, myths, structures, threats and opportunities.

From the 1800s we are showing works by J. C. Dahl, Peder Balke, Knud Baade, Hans Gude, Lars Hertervig, Kitty Kielland, Prince Eugen, Olaf Lange and Anders Beer Wilse. Except from the Swedish Prince Eugen all the artists are Norwegian. Many of the lived and worked abroad – foremost in Germany and France.

From our own time we are showing works by Per Kleiva (NO), Antony Gormley (UK), Mari Slaattelid (NO), Marte Aas (NO), Torbjørn Rødland (NO), Philip Andrew Lewis (US), Jone Kvie (NO), Tomás Saraceno (AR), Berndnaut Smilde (NL), Cory Arcangel (US), Matt Parker (UK), Sandra Vaka (NO) and Marie-Luce Nadal (FR). I addition we are collaborating with the international organization The Cloud Appreciation Society.

THE CLOUDS ARE NAMED

In 1802 the English amateur meteorologist Luke Howard classified clouds according to scientific principles and gave them Latin names. Howard’s system of cloud types is still in use today, but it has been expanded from seven to ten main types. Howard discovered that each type of cloud occurs at a different height in the atmosphere. Stratus clouds lie closest to the ground, and cirrus clouds are the highest. Cumulus clouds have vertical qualities and can therefore move through all the three atmospheric layers used by meteorology. Howard observed that cloud formation is influenced by the temperature and the sun’s location in the sky.

Photo: Oddbjørn Erland Aarstad

Read more about the ten main cloud types here.

This new teaching on clouds influenced several landscape painters. The Norwegian J. C. Dahl and the Englishman John Constable were very much inspired by Howard. They observed clouds closely and painted and drew hundreds of studies. On many of these, the place name, date and time of observation are recorded. The studies were intended as preparatory sketches for larger paintings.

J. C. Dahl, Stormskyer med regn, 06.08.1833. © Nasjonalmuseet

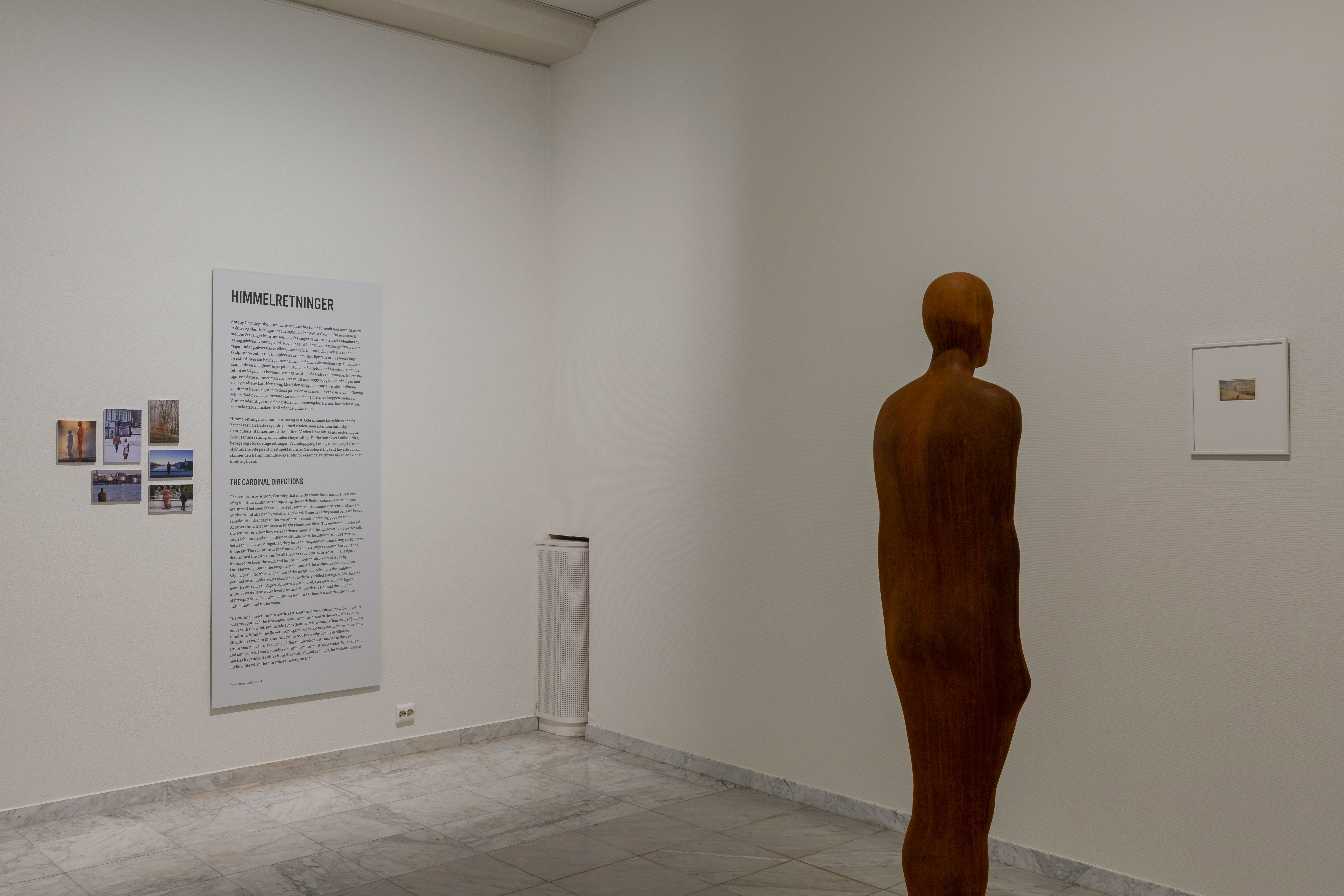

THE CARDINAL DIRECTIONS

Photo: Oddbjørn Erland Aarstad

The cardinal directions are north, east, south and west. Oftentimes, low-pressure systems approach the Norwegian coast from the ocean to the west. Most clouds move with the wind, but certain types (lenticularis, meaning ‘lens shaped’) almost stand still. Wind in the (lower) troposphere does not necessarily move in the same direction as wind in (higher) stratosphere. This is why clouds in different atmospheric levels may move in different directions. At sunrise in the east and sunset in the west, cloudy skies often appear most spectacular. When the sun reaches its zenith, it shines from the south. Cumulus clouds, for instance, appear chalk-white when the sun shines directly on them.

Antony Gormley "Broken Column" 2003

The sculpture in Stavanger Art Museum is just one of 23 identical figures that make up the artwork Gormley calls Broken Columns. The sculptures are all face north and spread between Stavanger Art Museum and Stavanger city centre. Many are outdoors and affected by weather and wind. Some days they stand beneath heavy rainclouds; other days under wispy cirrus clouds indicating good weather. At other times they are seen in bright cloud-free skies. The environments for all the sculptures affect how we experience them. All the figures are 1,95 metres tall, and each one stands at a different altitude, with the difference of 1,95 metres between each one. Altogether, they form an imaginary column rising 44,85 metres in the air. The sculpture at the front of Vågen (Stavanger’s central harbour) has determined the directions for all the other sculptures. In isolation, the figure in this room faces the wall, and for the exhibition, also a cloud study by Lars Hertervig. But in the imaginary column, all the sculptures look out from Vågen, to the North Sea. The base of the imaginary column is the sculpture perched on an under-water skerry next to the islet called Natvigs Minde, located near the entrance to Vågen. At normal water level, 1,49 metres of this figure is under water. The water level rises and falls with the tide and the amount of precipitation. Over time, if the sea level rises, there is a risk that the entire statue may stand under water.

Antony Gormley "Broken Column" 2003. Photo: Oddbjørn Erland Aarstad. From Domkirkeplassen, Arneageren and Vågen in Stavanger.

MANMADE CLOUDS

Humans have contributed to creating clouds of steam and smoke for thousands of years. With industrialisation and the invention of new means of transportation, several new types of clouds emerged. Polluting cars and trucks produce smog, while aeroplanes leave behind trails of condensation in the sky. The war industry is the origin of the most threatening of all cloud types: the mushroom cloud. The USA dropped two atom bombs on Japan in 1945. Since then, several nations have become nuclear powers. We now find ourselves in a tense situation, since some countries do not comply with disarmament agreements. Nine countries have nuclear weapons: the USA, Russia, Great Britain, France, China, India, Pakistan, North Korea and Israel.

Ander Beer Wilse

In 1909 the rail line Bergensbanen opened, with Finse as the highest point. For the first time ever, it was possible to travel the entire route between Bergen and Kristiania (Oslo) by train. And no longer were drawing and painting the best means for documenting the landscape: photography had developed to the point where it could capture speed and ephemeral elements. The photographer Anders Beer Wilse documented the modern invention of a rotary plough that scooped up and threw snow away from the train tracks at the same time as the snow became mixed with the steam from the locomotive.

Photo: Oddbjørn Erland Aarstad

Marie-Luce Nadal "Make Clouds Cry" 2017 (video)

Humans not only leave their mark on the climate, but also try to influence clouds. This is a theme Marie-Luce Nadal is interested in. Her approach is both scientific and laden with emotion. The film’s starting point is a tradition introduced in the 1950s in southern France, of ‘cloud seeding’ in order to keep hail clouds away from crops. At the same time, the approach is metaphorical because the ‘attack’ on the sky is intended to wound and induce tears.

Marie-Luce Nadal "Make Clouds Cry" 2017 (Still from video)

AEROCENE

The Argentinian artist Tomás Saraceno wants to push society in a sustainable direction. For 20 years he has collaborated with researchers specialising in a range of disciplines. He wants to understand the structures in clouds and spiderwebs and to see these structures in connection with the earth’s ecology, the atmosphere and the universe. Saraceno’s sculptures are filled with air and can be understood as metaphors for new ways of living and traveling.

Tomás Saraceno, "Biosphere" 2009. Photo: Oddbjørn Erland Aarstad

In 2007 Saraceno established the multi-disciplinary association Aerocene. Together, they have developed so-called aerosolar sculptures, which are balloons that rise and move through the air solely with the aid of wind and solar energy. The largest balloon can take a person up to the clouds. On 28 January 2020, Aerocene broke its own world records: on the salt flat Salinas Grandes in Argentina, a pilot rose to an altitude of 272,1 metres and flew 1,7 kilometres. The duration of the flight was 1 hour and 14 minutes. According to Saraceno and Aerocene, what today seemslike a utopia can become a reality in the future.

Photo of Aerocenes flight in White Sands, New Mexico, 2015.

DIGITAL CLOUDS

To an ever-greater extent, we live our life through social media and digital platforms. We programme, communicate and store data in ‘the Cloud’. Oftentimes the icon we click on to store or download digital data is a stylised cumulus cloud. In reality, the data is not floating in the atmosphere, but is stored on servers. The data for Stavanger Municipality, for example, is stored inside underground vaults. Located on the island of Rennesøy, the data centre measure 22,600 square metres and was formerly used as a NATO ammunition storage facility.

Matt Parker’s art project The People’s Cloud consists of six short documentary films and one sound work. The project explores the infrastructure of cloud computing. Parker interviews several industry experts in an attempt to make visible both the abstract and the palpable infrastructure that affects the entire planet but is still difficult to understand.

Sandra Vaka’s works link together images of physical and digital clouds. Her starting points are photos of clouds at sunset. These undergo a longer treatment: with an analogue camera, she photographs the pictures she sees on a computer screen from one to five times. But Vaka has either sprayed or painted water droplets on the computer screen. The droplets function almost like a magnifying glass. Through the process, the motifs are transformed, such that the finished pictures become combinations of steam, water, light and pixels. Printed on aluminium sheets, bent by the body and hung on the wall or lying on the floor, they point to the transformation clouds undergo and to the filters through which we see and interpret the world.

Video work: Matt parker "The People´s Cloud 2012-2020. Photography: Sandra Vaka "Clouds" 2020.

Cory Arcangel "Super Mario Clouds" 2002

The need to understand and master digital technology comes to expression in Cory Arcangel’s Super Mario Clouds. By hacking and changing the coding in a cassette for the popular video game Super Mario Bros (Nintendo, 1985), Arcangel removed the sound and all visual elements other than the blue sky with white cumulus clouds. What at first glance can be read as a nostalgic gesture, or as a stylisation of classical art’s cloud motifs, can also be understood as a resistance to participating is contemporary society’s high-speed digital development.