Michael Rakowitz

Proxies for Poets and Palaces

Michael Rakowitz (b. 1973) is an Iraqi-American artist whose practice examines the asymmetries of power between the Western world and the Middle East. Born and raised in the United States to a Jewish family that emigrated from Baghdad in the 1940s, Rakowitz draws upon his Arab-Jewish heritage to scrutinize Western interventions in the region’s conflicts. His works foreground the significance of cultural heritage in times of war and probe the ways in which societies negotiate the relative value of human life and cultural monuments.

At the centre of this exhibition are eight reliefs conceived specifically for Stavanger Art Museum, presented as a “room within a room.” These reliefs are reappearances of sculptures that once adorned the walls of a chamber in the Assyrian Northwest Palace of Kalhu* (near present-day Mosul). They form part of Rakowitz’ ongoing series The invisible enemy should not exist, initiated as a response to the looting of the Iraq Museum in 2003 following the American-led invasion of Baghdad. Rather than replicating the lost objects, the artist remakes them using discarded materials to evoke their absence. In this way, the artworks appear as “ghosts” of the originals—meant to haunt the viewer by serving as reminders of loss, rather than substitutes.

The exhibition further encompasses works that reflect on the role and fate of art and culture in the midst of war. Rakowitz’s practice spans subjects ranging from Assyrian antiquity to contemporary geopolitical struggles. Through an interplay of film, sculpture, and collected objects, he revisits historical events with acute sensitivity to nuance and contradiction. His oeuvre underscores art’s potential to disrupt entrenched imperialist modes of thought. This exhibition constitutes the first major survey of Rakowitz’s work in Norway.

*Kalhu is the ancient Assyrian name for the city later known as Nimrud in Arabic.

The invisible enemy should not exist (Northwest Palace of Kalhu), 2025

The series The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist is named after Aj-ibur-shapu, the main processional way into ancient Babylon, whose name has been rendered in one of several modern translations as “The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist”. Since 2007, Rakowitz has caused hundreds of artifacts looted from the National Museum of Iraq to reappear as artworks, both smaller objects and large-scale historic monuments.

For this exhibition, Rakowitz has recreated a specific chamber from the Assyrian palace complex at Kalhu, known as the “Northwest Palace”. Documented by archaeologists in the 19th century as “Room L,” this designation is retained by the artist. Built in the ninth century BCE by Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BCE), the palace became a site of extensive excavation and removal, with reliefs and objects dispersed across Western museums and collections.

The eight panels presented in this exhibition remained in situ until March 2015, when ISIS destroyed the palace in the wake of the US-led invasion of Iraq. The absences within the installation signify those panels taken abroad during the 19th and 20th centuries. Accompanying texts on the floor indicate the current locations of the displaced works.

Five of the reliefs depict winged figures known as apkallu – semi-divine beings endowed with wisdom and magic, who served as protective spirits in Mesopotamian mythology. In the Northwest Palace, apkallu figures were frequently carved with fish bodies or wings. In Rakowitz’s reappearances, each figure is headless; their heads were removed by archaeologists and sold to Western institutions who did not want to pay for the shipping of an entire stone panel. To underscore these historical acts of plunder, Rakowitz represents the missing segments as dark voids, mimicking the texture of the rough stone after the carved heads were removed.

Their vividly coloured surfaces are fabricated from humble materials such as newspapers and food packaging; their palettes derived from the originals, and sometimes departing from them to acknowledge the fact that the King would often have them repainted according to his whim. The use of West Asian and Iraqi packaging renders visible a culture largely made invisible in the United States of Rakowitz’s upbringing, while the fragments of disposable materials that contain the ingredients that feed and grow new generations of these diasporic communities simultaneously serve as emblems of survival.

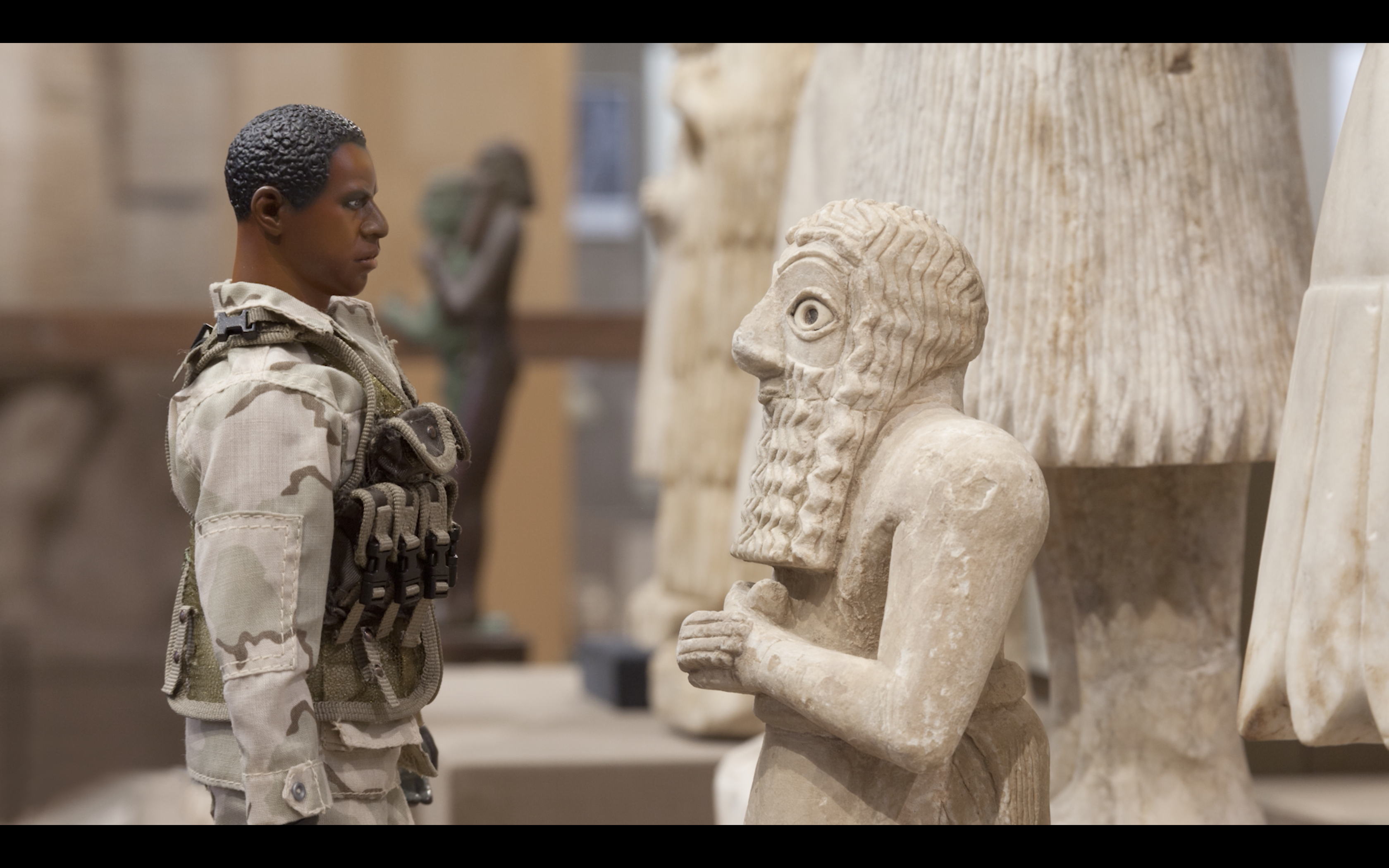

The Ballad of Special Ops Cody (2017)

This work takes as its starting point a 2005 incident in which an Iraqi insurgent group released an online image of a supposed American soldier named John Adam being held captive, threatening his execution unless Iraqi prisoners held on U.S. bases were freed. The U.S. military investigated but found no record of such a soldier. It was later revealed that “John Adam” was in fact Special Ops Cody, an action figure modelled on an American infantryman. Sold exclusively on U.S. military bases in Kuwait and Iraq, these toys were frequently mailed home to soldiers’ children.

The Ballad of Special Ops Cody plays off this story and gives life to the figurine through the production of a stop motion animation filmed at the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute, which has had a relationship with the National Museum of Iraq since the 1930s. In the animation, Special Ops Cody enters vitrines containing Mesopotamian votive figures taken during Western colonial expeditions. Though Cody urges the statues to leave and return home, they remain frozen –petrified and unable to return. The work probes questions of repatriation, a pressing issue within global museology, while simultaneously addressing the entanglements of American military interventions abroad.

What dust will rise? (2012)

Presented at Documenta 13 (Kassel, 2012), What dust will rise? comprises travertine-carved books, original artifacts, and a documentary film of a pedagogical encounter. The project was inspired by the Hessian State Library in Kassel, housed in the Fridericianum and destroyed in a 1941 bombing raid. Together with Afghan and Italian stonemasons, Rakowitz reconstructed the lost books in travertine from the Bamiyan valley, where two monumental sixth-century Buddhas were demolished by the Taliban in 2001.

The accompanying objects derive from histories of violence: the Kassel bombings, the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas, and a meteorite that struck Earth on 11 September 1954. Rakowitz foregrounds what endures once the dust has settled.

That same year, Rakowitz collaborated with Afghan sculptor Abbas Allah Dad, who had faced threats from the Taliban, and German sculptor-restorer Bert Praxenthaler. Together they convened a seminar with local students in a monastic cave near the niche of a destroyed Buddha. Since then, students have developed a new sculptural practice rooted in Hazara cultural heritage, their works also shown at Documenta 13.

I’m good at love, I’m good at hate, it’s in between I freeze (2009–)

In this ongoing project, Rakowitz investigates the intersections of art and politics, guided by his engagement with the work of poet and musician Leonard Cohen.

In 2009, the artist attended a Cohen concert in Chicago, his first encounter with the renowned Jewish singer-songwriter. Deeply moved by Cohen’s humility and lyrical resonance, Rakowitz later followed the controversy surrounding Cohen’s planned 2009 concert in Tel Aviv. Pressured by pro-Palestinian advocates, Cohen sought to balance his appearance with a parallel concert in Ramallah. Amid accusations of tokenism, the Ramallah performance was boycotted and ultimately cancelled.

As a Jewish supporter of the Palestinian Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel (PACBI), Rakowitz questioned Cohen’s position while reflecting on the efficacy of cultural boycotts. Considering his own Arab-Jewish heritage, he contemplated restaging the cancelled Ramallah concert himself. Acquiring Cohen’s Olivetti typewriter via eBay, he drafted a script imagining the unperformed concert and wrote Cohen a letter seeking permission to perform the songs – a request that remained unanswered.

Originally presented in the context of a 2017 exhibition honoring Leonard Cohen in Montréal, Cohen’s manager declared the film unsuitable and revoked Rakowit’z rights to Cohen’s music. Six years later, Rakowitz and his co-director Robert Chase Heishman restored the work in a new form, commissioning a new soundtrack from musician Bill McKay, and including voiceovers from friends in Palestine and beyond who describe what is lost in the sections where Cohen’s music has been silenced. The title, I’m good at love, I’m good at hate, it’s in between I freeze, derives from Cohen’s Recitation. The project exemplifies Rakowitz’s ability to uncover connections, tensions, and unresolved narratives through the close examination of singular historical events.

The invisible enemy should not exist (Lamassu of Nineveh) (2018)

In 2018, Michael Rakowitz reconstructed a destroyed lamassu – a protective deity combining a human head, bull’s body, and bird’s wings. The work forms part of the ongoing project The invisible enemy should not exist (2007–) and was realized as a commission for The Fourth Plinth project at London’s Trafalgar Square.

The original guardian figure, nearly 3,000 years old, was installed at the Nergal Gate of Nineveh (present-day Mosul), erected in 700 BCE by King Senecherib. While many works from Nineveh were removed to Western institutions during the 19th and early 20th centuries, this sculpture was destroyed by ISIS in 2015. Rakowitz’s version was clad in the bright surfaces of Iraqi date syrup cans, the colours referencing the original polychromy while the material choice evokes the devastation of Iraq’s once-flourishing date industry as a consequence of war and imperialism.

During the summer of 2025 (23 May–8 September), the sculpture was installed outside Stavanger Cathedral as part of the city’s 900th anniversary celebrations. Stavanger Art Museum sought, through this gesture, to forge connections across time and cultures, to express solidarity with those affected by war and displacement, and to affirm the importance of safeguarding our shared cultural heritage and the people to whom they belong.